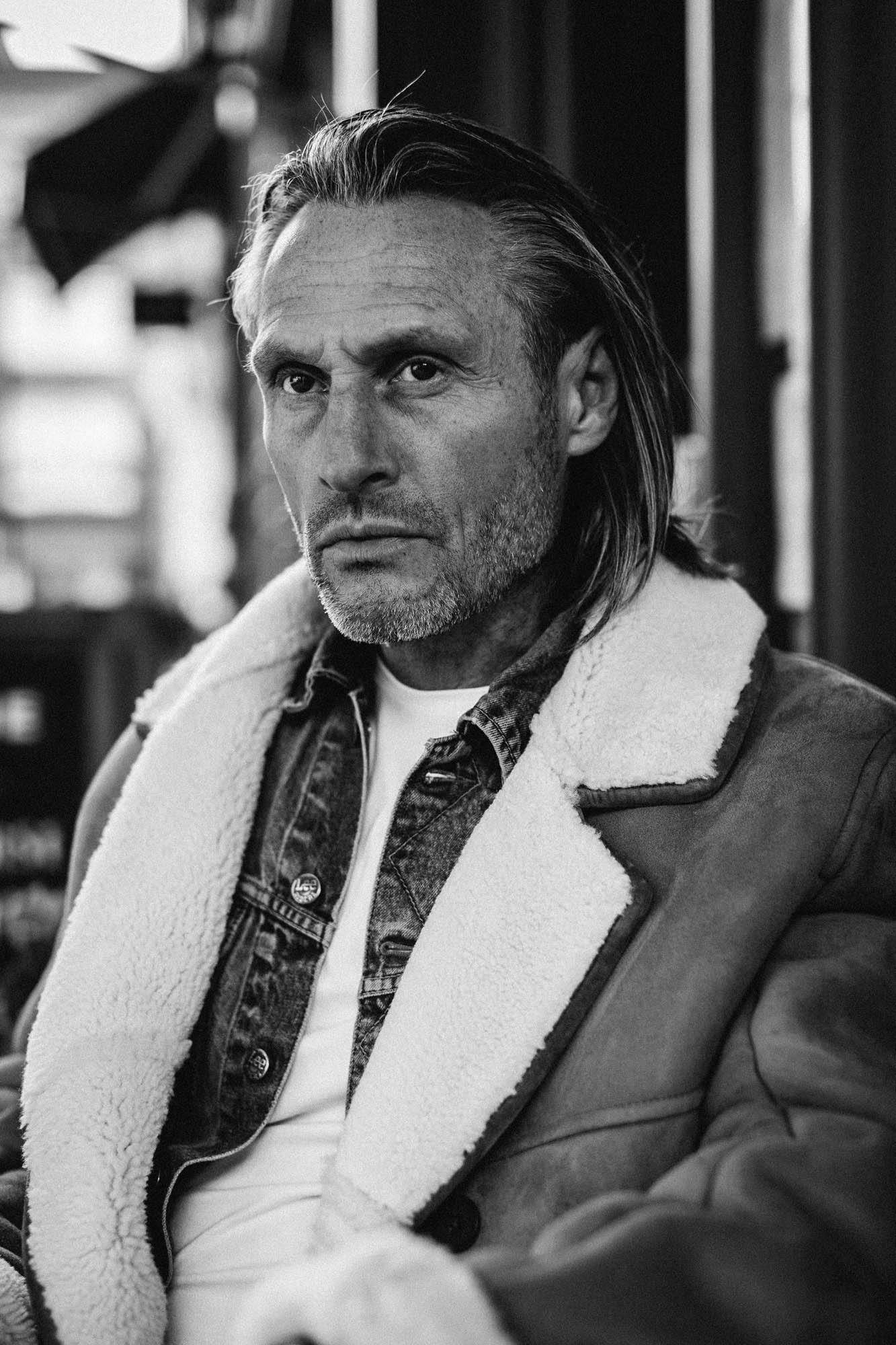

The distance from Islington to Bloomsbury as the drone flies is less than three miles, but Gary Kemp has come a long way. He and his younger brother, Martin, a fellow actor and member of the band Spandau Ballet, used to live with their parents on the middle floor of a three-storey Victorian terrace, with a single outdoor toilet that was shared by the entire household. (The top floor was occupied by his aunt and uncle, and the bottom by his cousin’s family.) The property didn’t even have electricity until a year after the elder Kemp boy was born; the brothers washed in the kitchen sink, or at the swimming baths.

Today, Kemp’s less humble abode is a six-bedroom Georgian townhouse that would rival some museums. “I’ve always liked more traditional style,” says the 58-year-old New Romantic trendsetter. “As you can see, I got really into Victorian arts and crafts.” At 22, he used his first significant pay cheque from Spandau to purchase a chair created by architect Philip Webb in 1860 for the company established by the celebrated 19th-century designer William Morris. It was the first piece of owned furniture in a family where “everything apart from the cat” was on hire purchase. Still living at home with his parents, in a “modernised” Victorian terrace up the road, Kemp put his statement piece into storage.

Kemp, who also became the first member of his family to buy property, is now the proud owner of probably the UK’s largest collection of works by EW Godwin, the architect-designer who imagined all of Oscar Wilde’s furniture and JM Whistler’s house. (Some of Kemp’s pieces have been to New York and back for exhibitions.) Godwin et al were part of the Aesthetic movement, a loose collective of creatives in diverse mediums who championed beauty. “It was quite a camp scene, people wearing knickerbockers and velveteen,” says Kemp, who likens it to the youth culture that Spandau later embodied: “Instead of music they had poetry, and instead of making videos they made furniture.”

Kemp holds vigorous opinions on aesthetics. “I would never would dream of having an interior designer anywhere near me,” he says, declaring himself “obsessed” with having everything in its right place, levelly hung. “And if it isn’t, I can’t think straight.” He compares it to “getting your suit right” and confesses that he gets “a little bit upset” when he sees someone with overlong sleeves or incorrectly turned-up trousers. “I’m not always like that,” he adds, conscious of his self-confessed control freakery.

“Clothes can convince you that you’re someone you’d like to be. And, I suppose, being an actor as well, I have a propensity for that even more”

That Kemp puts great deal of stock in his attire is clear from the first page of his searingly honest 2009 autobiography, I Know This Much: From Soho to Spandau. Like the band’s oeuvre, Kemp wrote it all himself, causing him pride and pain. The story begins with Spandau’s ostensible end: the 1999 court case in which the three members of the band who weren’t related to Kemp sued him for a cut of songwriting royalties. They lost, but Kemp disputes the verdict that he “won”; they were estranged for 20 years until the band reformed in 2009. They embarked on a world tour in 2015 and remain together, although singer Tony Hadley departed under a cloud last year.

Getting dressed for court is the real trial. Perspiring, Kemp agonises over his choice of shirt – pink is “too presumptuous, a little cocksure”, white is “more sober” – and the length of his tie, which is “a noose around his neck”. Clothes, he writes, “had always been an obsession”. His aesthetic preoccupation can be traced back to his father, who was “quite artistic” and made his children everything from model airplanes to a dulcimer. Kemp senior yearned to become a journalist, but was forced by economic necessity to leave school at 14 and become a printer. He wore a tie and jacket, which he exchanged at work for a thin brown overcoat that, Kemp junior writes, “transformed him like the suit of a superhero”.

“It’s odd, really, that I ended up being drawn towards the suits of the upper classes,” he continues. Proudly working-class but fiercely aspirational, which left him “a mass of neurotic contradictions” as he achieved success, Kemp was born within earshot of Bow bells and starred with his brother in the 1990 film The Krays. He doesn’t, however, sound like an East End gangster. He later appeared in 1993’s Killing Zoe, produced by Quentin Tarantino; the director told him that he’d handed the crew of 1992’s Reservoir Dogs tapes of The Krays, with its highly stylised black suits and ties. Kemp was sent the script but didn’t get a part; he did, however, imitate life as an oily music PR in The Bodyguard (also 1992).

Then again, Kemp’s fascination with wardrobe of the aristocracy isn’t that odd, really. “When you put on a suit like that, it’s a bit like creating a character for yourself,” he says of his English Cut commission. “Clothes can convince you that you’re someone you’d like to be. And, I suppose, being an actor as well, I have a propensity for that even more.” Before he found fame as Spandau’s lead guitarist and creative force, Kemp was a child actor in films and part of the same youth-drama club as Linda Robson and Pauline Quirke from sitcom Birds of a Feather. Dressing up is very literally theatrical for him and his wife Lauren, a costume designer and stylist with whom he has three young sons: they reserve their finery for going to a play, or for a meal.

Clearly his wife is someone with a strong aesthetic, which begs the question of who decides which trousers get worn in this most particular of houses, never mind who wears them. “She wears the trousers all the time,” he laughs. She lets him dictate the position of objects, but they go antiquing in unison. And when it comes to clothing, even if he knows his own taste, he shops with her in mind: “If I buy something to wear and she doesn’t like it, then it stays in my wardrobe forever. Because the first person I want to appeal to is her.”

At his English Cut fitting, Kemp plumped for a grey double-breasted suit in Prince of Wales check with an uncharacteristic measure of uncertainty: “I don’t know why – probably because I’ve got a wardrobe full of blue.” The end result is “very London”, with a pleasing 1940s vibe, while the pleated trousers – at English Cut’s recommendation – take him back to the 80s, when he last wore that style. The figure-hugging fit also contributes to the garment’s transformative effect. “If you’re wearing a smashed-up linen suit, you’ll walk like a novelist in the 50s; if you’re wearing a suit that’s very sharply cut, you’ll have a different gait,” he says. “That’s a thing that I’ve always liked about clothes.”

He also likes the fact that his suit was made in his favourite part of the world, Cumbria. “We go up to the Lake District three times a year,” he says. “We’re big walkers.” His eldest son Finlay, from his marriage to his first wife, actress and model Sadie Frost, is a keen mountaineer. Kemp has also become obsessed with cycling, and the aesthetic perfected by the brand Rapha, thanks to an endorsement from his friend, the journalist Robert Elms: “He said to me, ‘I just had a fitting that took three hours – and it was for a bike.’” Elms was the man who gave his band their name after seeing the phrase “Spandau ballet” scrawled on the door of a nightclub toilet in Berlin.

Kemp’s first commission, circa 1970, was a pair of on-trend two-tone trousers in rust and green by an East End tailor that his dad took him to. “I remember this mole-like guy who had really thick glasses and a great big set of scissors, and chalks, and tape around his neck,” recalls Kemp. Even then he had a clear sartorial vision. “I needed them to be of a certain parallel width. Parallels were happening, so they were the same all the way down, they didn’t tighten or flare.” He teamed them with brogues that he placed carefully so that they were the first thing he saw when he woke up: “They were totemistic, something that connected me with adulthood. And they were like a piece of art: really beautiful.”

The pub next door to Kemp’s childhood home, The Duke of Clarence, was a watering hole for immaculately suited and scootered mods, who made an impression on the youngster. Another of his early sartorial memories is going to a shop in Angel run by two ex-mods to buy a Brutus shirt. (He wanted a Ben Sherman.) “This bloke took me to the back, and there were all these shirts in these wonderful pastel colours, like Neapolitan ice cream: sky-blue, lemon and pink,” he recalls. Giddily, he chose lemon: “The cellophane was unwrapped, and out this beautiful colour cascaded.” Kemp also acquired a jacket like that of Adam Faith on TV show Budgie, but he didn’t essay the white clogs.

The young Kemp thought he looked “the business”, but looking back, the older one deems it “playground fashion”. “I think what it was about was finding a uniform that could connect you with a certain set of people,” he says. The middle-class kids at his grammar school were into prog rock and not dressing up. Kemp had his aspirations intellectually and artistically, and his secret Genesis and Yes albums, but that world was “a bit dull visually”. That left two tribes, both mod descendants: “the Rod Stewart lot”, which was the working-class mods who went skinhead and suedehead; and glam rock, the aspirational, middle-class mods – where the real dressing-up was going down.

“Bowie was a big moment for me,” says Kemp, who handed him a bangle from the front row of the Hammersmith Odeon and enjoyed brief eye contact. Androgyny was a leap for his parents’ generation, barely used to men with long hair, which was of course its appeal to their offspring. The next jump was punk, which didn’t strike a chord with Kemp. “I always felt that was a real middle-class kind of idea of what the working classes should look like,” he says. Instead, he gravitated towards New York-inspired soul boy, a look Bowie adopted for his 1975 album, Young Americans.

By this point, Kemp had formed a band with fellow pupils Steve Norman, John Keeble, Michael Ellison and Hadley. They called themselves the Gentry in reaction to punk: “We were saying, ‘We’re working class, but we don’t need to dress like that. We spend every penny we have on clothes, caring for them and making sure they’re not smashed up in a pub.’” The problem was the name and the look. They’d been through the power-pop phase, silk-printing their own pop-art T-shirts after seeing Generation X perform. Then they found soul boy, but even with their wedge haircuts, small buttoned-up collars and waistcoats from Woodhouse, they were still playing power pop.

Their keen-eyed manager, Steve Dagger – a musically savvy school friend of Kemp’s who admired the way that the Who’s manager, Pete Meaden, had repackaged them to appeal to a mod audience – had spotted how every scene had a band. Punk had the Sex Pistols, glam had Bowie, psychedelia had Pink Floyd. Kemp and co just needed a scene.

Dagger identified the Bowie night at Soho nightclub Billy’s, which was frequented by students from Central Saint Martins college of art and design dressed as “futuristic cossacks”. They either bought their sci-fi garb from a shop called PX or made it; Kemp and his brother duly drew the outline of a pair of fly-less peg trousers on paper and got their mum to cut and sew two corresponding pieces of material together. Kemp also bought a shirt fashioned by one of the club-goers, who wrote his name in the collar in felt-tip pen: “GALLIANO”. The “costume box” couture was also sourced from Oxfam and secondhand shops; the Evening Standard dubbed the crowd “dandies in hand-me downs”. Dagger also insisted on replacing Richard Miller, who himself replaced Ellison, with Kemp’s brother, who didn’t even play bass, arguing, “He’s the best-looking bloke we know.”

The Soho club scene was an explosion of creativity from which emerged Bananarama, Animal Nightlife, Midge Ure of Ultravox and Wham! (Club Tropicana was written about Le Beat Route, another haunt of the Blitz kids.) And that’s just the musicians. Other notable alumni include: milliner Stephen Jones; David Holah and Stevie Stewart, who established the fashion label BodyMap; designers Melissa Caplan and Stephen Linard; stylists Chris Sullivan and Perry Haines (the latter also co-founded the magazine i-D); photographer and graphic artist Graham Smith; Robert Elms. The waspish cloakroom attendant at Billy’s who teased the Spandau lads that he could sing better became Boy George.

Nevertheless, Spandau were installed as the band of what the media christened New Romantics, painting them as decadents or even Thatcherites (despite the fact that they were anything but) in order to wind up their readers. Spandau cannily snubbed the snooty music press and played the mainstream organs like a fiddle to reach a wider audience. Soon, high-street stores were knocking off their look; Princess Diana wore knickerbockers and pie crust-collar shirts. They upped the ante for their 1983 True tour with zoot suits. When their bags were rerouted ahead of a gig in Porto, they turned their hotel bedsheets into togas; the next night in Lisbon, the crowd did as Romans do.

What dissolved Spandau, which had already started to disband, was the arrival of acid house. “You didn’t need to wear anything other than a tracksuit and trainers, because you were so involved in the ecstasy,” says Kemp. Britpop followed, and also disappointed Kemp, for whom music is a “visual feast”. Today, the biggest musical influence on style is rap, but it’s a far cry from when Top of the Pops and MTV pervaded all. By far the widest avenue of self-expression is social media: “Everyone can be creative now – you don’t need to form a band.” The would-be fashion-museum pieces that Kemp so fearlessly pioneered with his peers were unceremoniously donated to Oxfam.

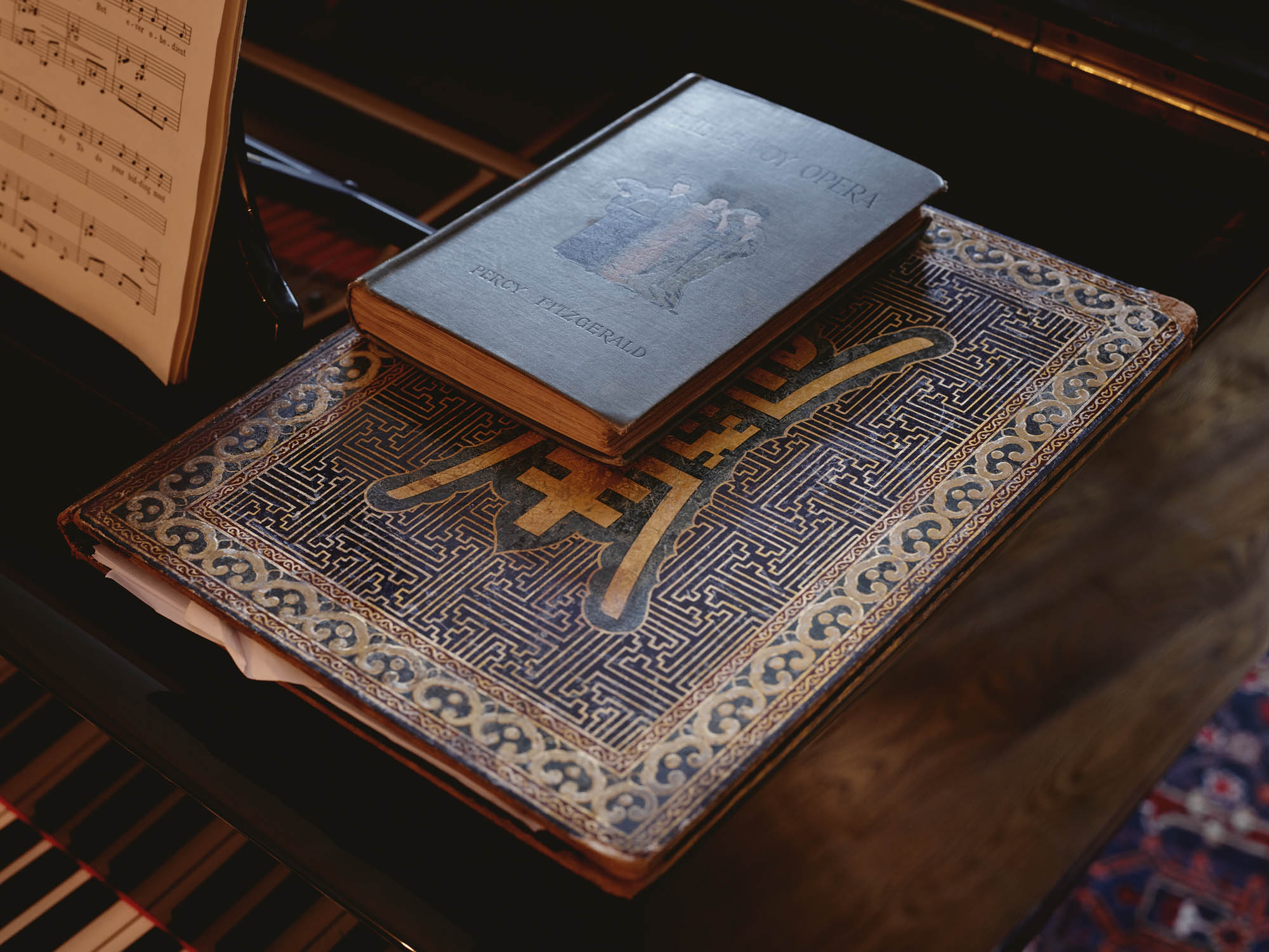

Kemp also admits to causing rifts with his pursuit of acting and his possessiveness of songwriting responsibilities. In retrospect, he needn’t have worried: in 2012, he was awarded an Ivor Novello award for outstanding song collection. He’s written a musical based on the life of WB Yeats and is currently working on three projects: one for the stage, two for bands. He’d like to release a follow-up to his 1995 solo album, Little Bruises, but lacks the confidence, which is why he shied away from being a frontman: “I write a lot of songs and put them away.”

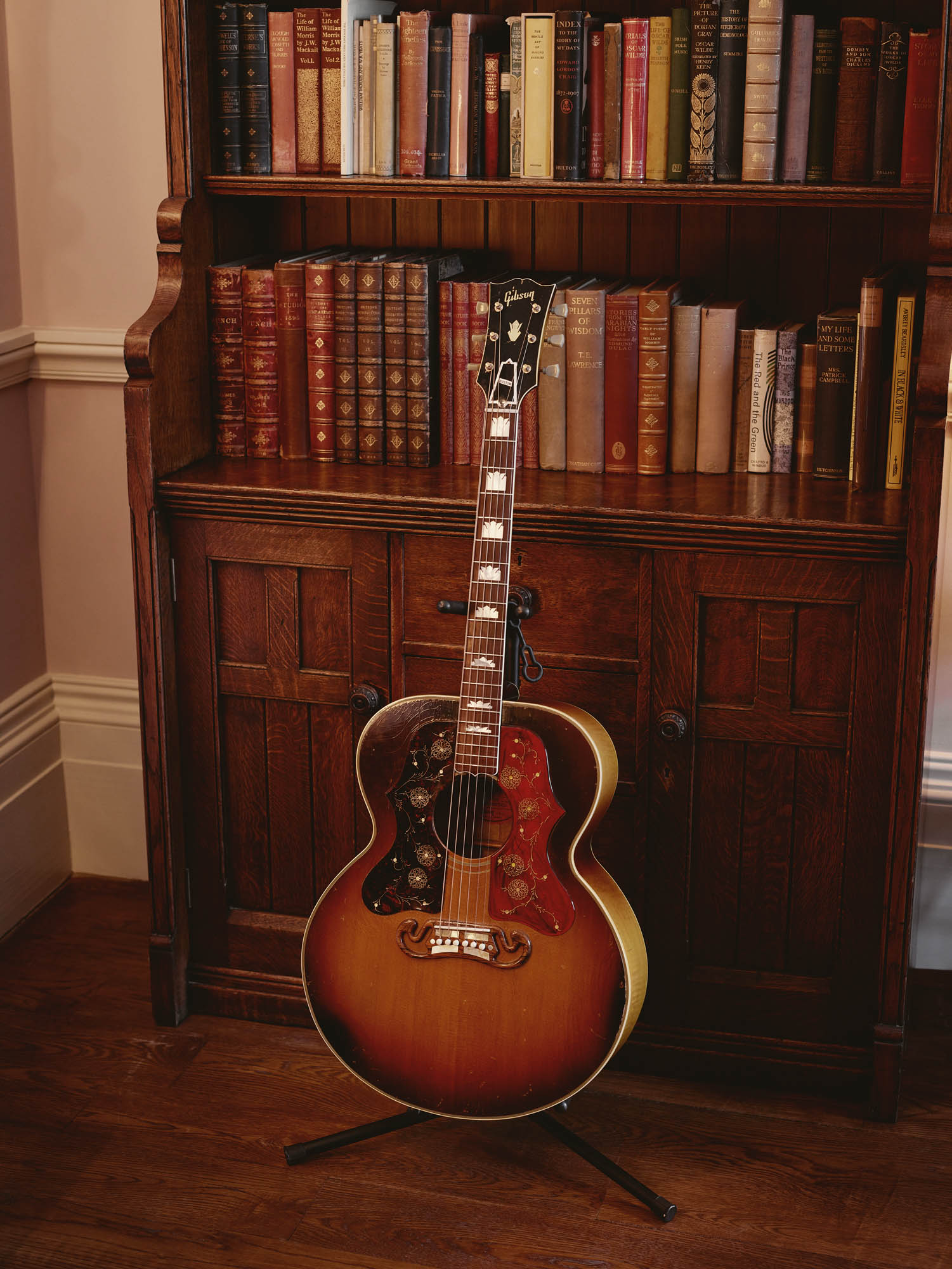

Initially disappointed with the gift of a guitar on his 11th birthday, within three months Kemp had written two songs. The process begins with instrument in hand and a melody, which keys him into a thought; it begins in the heart and proceeds to his head. Unsurprisingly, Kemp is not the sort of person to bung loads of stuff down indiscriminately, and finds it hard to work with those who are. “A song’s got to have order,” he says. “I like neatness.” He draws a parallel between a finished song and a different kind of arrangement: “It’s like walking into a beautiful house. Wherever you look, there’s something of interest, but it has its own space to stand out and be admired.”

In a sense, he feels he’s lost ownership of his biggest hits, such as True and Gold; they belong to everybody, having gone out into the world and gained their own independence. Writing a song is, he says, “like creating a being”. Speaking of which, how is Kemp able to maintain such a beautiful, neat house when he shares it with three young children? “There are spaces that are more adult-oriented and spaces that are more kid-oriented, but it’s quite hard for me, put it that way,” he laughs. “They have a playroom that I can’t go in. My wife’ll tell you: I can’t walk in there unless it’s all tidied up.”