Being in GQ editor Dylan Jones’ office can be an intimidating experience – even more so than sitting downstairs with all the female models in the lobby of Vogue House in London’s Mayfair. The reverent hush that hangs over the church-like main GQ office on the first floor spreads to the Cork crew as they wait for their subject to arrive.

On the wall behind Jones’ desk are edited highlights of his 18-year tenure at the helm of the monthly style bible – most obviously, a king- sized cover of the May 2012 issue graced by Prince Harry. Following a recent visit by Alastair Campbell, the former New Labour press secretary turned GQ’s chief interviewer, some of the frames bear pink Post-it notes with his scrawled verdict on their respective coolness. A Daily Mail front page with David Cameron and Nick Clegg. An Evening Standard front page featuring a picture of Boris Johnson – the magazine’s one-time car correspondent – with erstwhile wardrobe mistresses Trinny and Susannah at the annual GQ Men of the Year awards. A letter on 10 Downing Street-headed paper from Cameron, thanking Jones for his work on the 2008 book Cameron on Cameron: Conversations with Dylan Jones, published shortly before the now-Brexited prime minister came to power.

Also chairman of London Fashion Week Men’s for 10 seasons, Jones is an “influencer” in a sense that few labelled such merit. His endorsement can make or break aspiring fashion designers and prime ministerial hopefuls alike – or certainly embarrass them with revelations about, say, how much they drink (William “14 pints a day as a teenager” Hague) or fornicate (Nick “no more than 30 women” Clegg over). More than anything though, The Cork’s collective nervousness probably stems from the fact that Jones has a keener assessment than most subjects of the quality of photographers, stylists, creative directors and yes, interviewers.

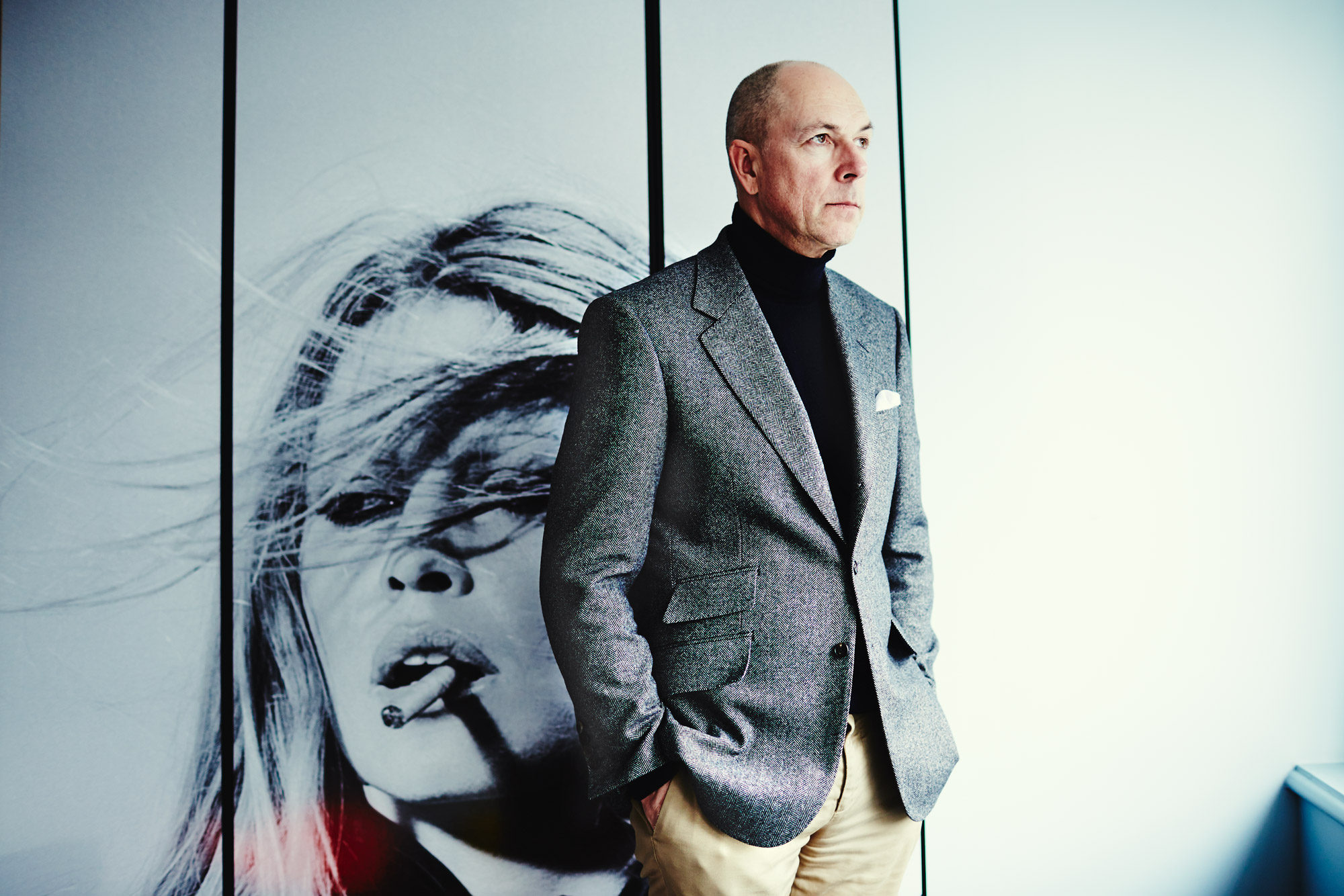

Jones sweeps in and puts the assembled slightly more at ease before removing his overcoat to reveal his English Cut sport coat in a grey herringbone wool/cashmere mix. Unsurprisingly, given his various professional hats, Jones is no stranger to being tailored. “Before London Fashion Week Men’s, we usually receive a visitation from some Asian journalists,” he says. “They ask questions like, ‘What is your style regime?’ in the expectation that I will give a really interesting answer. And I say, ‘Well, I get up in the morning and I put a navy-blue suit on.’” Which explains why, in this case, he broke from the normcore: “It’s really well made. Fantastic cloth.”

Jones’ reputation proceeds him, but while his stature and appearance – tall, bald, tailored – command respect, he’s no totalitarian dictator. Many of his staff at GQ have been there almost as long as he has; if he rules with an iron fist, it’s ensconced in a bespoke velvet glove. And behind the faintly imposing aspect lies a wickedly funny sense of humour, often at his own expense. “I’m sure that people used to think it was an affectation, but I started having suits made in the early 80s, when I was 24 or 25, because I’m really narrow and skinny – not as skinny as I used to be, unfortunately,” he says. “Back then, you couldn’t get any suits off the peg to fit you, because they were all very wide, boxy, double-breasted jackets with big shoulder pads. They looked like someone had thrown a bedsheet over a beanpole.”

Since then, Jones has accumulated a “disgusting amount” of suits. “Too many,” he admits, although he refutes (semi-serious) allegations that his office was extended principally to accommodate them: “No. All right, maybe … But the thing is, people with large wardrobes usually have a lot of everything. I just have a lot of suits, and they’re all exactly the same: navy-blue.” Decision-fatigued high-fliers will often adopt a uniform so that they have one less thing to think about every day – like Barack Obama, who famously told Vanity Fair that he only wore navy or grey suits, or Steve Jobs, who had a job lot of identical black turtle-necks by the Japanese designer Issey Miyake. Or, suggests Jones, the Italian architect Gio Ponti: “He had four suits that he used to wear all year round: two for winter, two for summer; one for day, one for night. Brilliant. You just want to put a suit on, go to work and not worry about it.”

“Journalists ask questions like, ‘What is your style regime?’ And I say, ‘Well, I get up in the morning and I put a navy-blue suit on’”

Irrespective of any professional requirement, Jones wears suits because he likes to, and because they suit him. But his conversion to tailoring was in part a career decision. “I used to edit a magazine called Arena and I left that in 1992 to become associate editor on The Observer,” he says. “I thought, ‘If I’m going to work in newspapers, I should start wearing suits.’” Having not yet achieved a sufficiently high stature for Savile Row, his first tailor was Jack Geach in Harrow, who made drape jackets for teddy boys. From there, Jones moved up a division to Chris Ruocco, an ex-boxer in London’s Kentish Town who was in the corner of hit artists such as Spandau Ballet and Wham! “One particular pop star used to call up a shop on South Molton Street called Bazaar and get a load of clothes delivered to try: Yohji Yamamoto, Comme des Garçons, things like that,” says Jones. “He’d buy one piece to make it worth the shop’s while, then he’d send the rest to Ruocco to be copied.”

Later, Jones became interwoven with Timothy Everest, one of the driving forces behind the New Bespoke Movement of the mid-90s that injected a bit of fashion designer adrenaline into the flatlining craft. “Then Sarah Brown, who’d just married Gordon, wanted to make him look more elegant, so I recommended Timothy Everest,” says Jones. “Tony Blair got so jealous of Gordon’s suits that he started having his suits made there.” Jones shifted his own allegiance to Richard James, another of the Cool Britannia tailors who made his suits for some time, including for his own wedding.

The other benefit of a uniform is that it removes the need for the kind of potentially disastrous experimentation that Jones used to conduct. “I used to wear awful things: tank tops; shirts with butterfly collars and French cafe scenes; bottle-green, high-waisted pinstripe trousers,” he grimaces. “My worst purchase was some platforms. Can you imagine me in platforms? I was 6’1”: I didn’t need the extra five inches. And they were two-tone beige, sort of like brown and cappuccino. I bought shoe paint and painted them two shades of green. So I had green pinstripe Oxford bags, some sort of green top and these two-tone green platform boots. I mean, disgusting.”

Jones’ sartorial awakening occurred at the age of 12, when he saw David Bowie on Top of the Pops: “Some people wanted to go and see Bowie; some people wanted to dress like him. I wanted his hair.” Alas, the unisex hairdressers of the Kent town of Deal, near Dover, were far from cutting-edge. “Of course they’d never heard of Bowie,” says Jones. “And when I showed them a picture, they said, ‘There’s absolutely no way that your hair can look like this because it’s floppy, not standy-uppy.’ I left looking like Dave Hill from Slade.” However, his one successful attempt to glam-rock up his life was a selection of brightly coloured glittery socks.

It’s hard to imagine given his conservative, statesmanlike mien – less so if you look at the evidence that he periodically posts on Instagram – but Jones was quite avant-garde in his youth. He studied graphic design, film and photography at London’s St Martin’s School of Art during the height of the Blitz – the nearby club, that is, with its art student clientele, the breeding ground for cultural movements such as New Romanticism. Jones was focused on becoming a photographer; the only problem was that he was “terrible”. “One of my degree projects was a pornographic Action Man series: all these toys having sex with each other,” he says. “I’ve got lots of photographs of all the people involved in the Blitz era, but I wasn’t very good. I wish I’d persevered though. I probably would have made a lot more money.”

Never intending to go into journalism, much less the “style press”, Jones’ entry was unorthodox. “I was working on the door of the Gold Coast Club on Meard Street, underneath the Batcave,” he says. “A friend of mine called Mark Bayley was taking pictures for i-D magazine and needed someone to go and ask the subjects how much they hated Margaret Thatcher and what kind of socks they were wearing. As I had nothing to do that day apart from get up late and watch Channel 4, I went along, typed it up on an old red typewriter and sent it in. Then I found out, because I didn’t have a telephone, that Terry Jones – who owned i-D at the time – was trying to get in contact with me. He offered me a job and basically ‘invented’ me by giving me a career.”

Jones rose to become editor at i-D in 1984 before taking over at Arena in 1988 after a stint as contributing editor to The Face, which was hugely influential in its heyday, but now – like Arena – is sadly defunct. Following his time at The Observer, he moved to The Sunday Times Magazine in 1993, again as associate editor, before returning to magazines proper in 1996 as group editor of The Face, Arena and Arena Homme Plus; and papers in 1997 as editor-at-large of The Sunday Times. When he became editor of GQ in 1999, his glossy new environs soon bore the telltale fingermarks of newsprint.

“Andrew Neill had reinvented The Sunday Times basically by copying lifestyle magazines,” says Jones. “So I thought we should go the other way and copy newspapers. We hired the best writers we could afford: Adrian Gill, Tom Wolfe, Dominic Lawson.” Jones’ back-of-cigarette-pack pitch for his GQ editorship was “AA Gill directs a porn film”, which he delivered on: “Adrian wrote this amazing script full of people having sex on and with various types of food. Very funny. Then he went off to California to make the film. By the way, when the tapes came in they disappeared like that.”

There was a serious point to all of this. GQ already had a reputation as a yuppie handbook, “fantastic for fashion and fancy restaurants.” Jones’ brainwave was to bolster the style with some substance. “The idea was to bring really good, longform feature writing and intelligent criticism to the magazine, because it wasn’t being done elsewhere,” he says. Certainly not by the lads’ mags that were dominating the “brutal” market. Investing in quality proved a sound strategy, then and now: while GQ’s circulation has eroded in line with the wider shift from print to digital, it has remained fairly solid at around 115,000 a month; the likes of Loaded and FHM, meanwhile, dropped off a cliff from their height of 1 million – and did not survive the fall.

In this brave new world of 24/7 streaming content, quality is more important than ever, says Jones. “Everything’s flat,” he says. “Most things are free and available on your phone. If we drop our quality, we won’t deserve to survive because there’s so much stuff out there.” Even in print, exaggeratedly rumoured to be dead on a daily basis. “I’ve just been in Selfridges and the WHSmith concession is full of magazines,” he says. “And if you want to know how to do a bow tie or what watch to buy, you just open up your phone. So why on earth should people buy GQ? You’ve got to work harder than ever before to make sure that what you do is better than everything else.”

Jones has played his part in this content deluge. As well as the Cameron tome, he’s penned biographies of Paul Smith and Jim Morrison, plus iPod Therefore I Am: A Personal Journey Through Music and Mr Jones’ Rules for the Modern Man, an etiquette guide that was “particularly popular in Asia and the ‘Stans”. He wrote three books in 2012 alone: The Biographical Dictionary of Popular Music, From The Ground Up: U2 360° Tour Official Handbook and When Ziggy Played Guitar: David Bowie and Four Minutes That Shook the World. This September sees the release of David Bowie: A Life, a biography assembled from a series of Jones’ own interviews with the Starman and 180 of Bowie’s “friends, rivals, lovers and collaborators”. When asked, in the manner of someone patronising a successful woman, how he makes it all work, Jones – a father of two – says, “I just get up very early. And I don’t have hobbies.”

Currently on Jones’ desk is a copy of his new coffee-table book coming out this spring, London Sartorial: Men’s Style From Street to Bespoke, which “will hopefully generate some interest in what we do”: namely, Jones’ patronage of London Fashion Week Men’s, which has earned him an OBE. If you didn’t know his background, you might imagine that this suit-wearing establishment figure is bemused by some of the more “directional” offerings on the capital’s catwalks. But they’re the juice that keeps the city’s menswear uniquely fresh, the wham-bang yang to tailoring’s steadfast yin.

“London is brilliant at tradition and brilliant at rebellion; it’s the mixture of the two,” he says. “There are amazing brands in Milan, but name me one Italian designer under the age of 50. Even the young designers in New York can’t get on the first rung, because the department stores are too scared to stock them. In London you’ve got an integrated system where the young designers are supported by the industry.”

Meanwhile, the “extraordinary allure” of Britain’s tailoring heritage to the far east – which Jones confesses he completely underestimated at the outset – has given a huge fillip to London Fashion Week Men’s, the energy of which has in turn rejuvenated Savile Row and its ilk. “About 20 years ago, I went to have a coat made and it was like Night of the Living Dead – all these old people who looked like they were about to expire,” says Jones. “I took it back to be altered 15 years later, and the place was bouncing.”

New blood is vital for remaining relevant; Jones employs “very young, very cool people” to ensure his finger remains on the pulse. But his daughters also help to keep his ear to the ground, culturally. “Until recently, the only sanctuary I had for playing music was the car,” he says. “Not anymore, because they just go, ‘Oh God, it’s so embarrassing.’ So I listen to what they do, which at the moment is Chance the Rapper, Drake and Frank Ocean.” Sure enough, the latest issue at the time of writing includes a feature on Frank Ocean. Perhaps he should increase their pocket money.